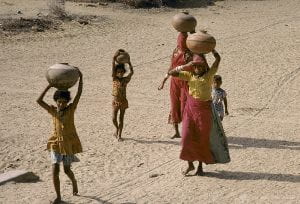

Environmental degradation is a widespread issue for the Global South that has impacted females arguably more than any demographic in these nations. In my post from last week, I discussed the negative impacts of climate change that women face in Third World nations. From living in agrarian societies where women are mostly relied on as the sole providers of sustainable food sources, degradation of the environment has put a large strain on the food sources for many (Daza 1). Leading into the discussion on drinking water in the Global South, women experience the same types of oppression when it comes to food and water. With a lack of resources, women and female children are forced to travel often far distances to provide their families with necessities because it is a societal expectation of them. Women and young girls travelling for resources increases the risk of physical danger and health issues, and decreases the time that women may spend doing other such things like getting an education (UNWater 1). On top of being expected to take on sustaining their families, women are also limited with work due to less job opportunities, leaving them with seasonal agricultural jobs that yield little in sustenance (UNWater 1). When reading the interview with activist Vandana Shiva, she discusses her experience with the impacts that deforestation had on peasant women in India. Shiva stated that these peasant women were well versed in what nature had to offer them, but with the forests being cleared, these women no longer had the trees and plants needed for food sources, firewood, and medicinal purposes (London 1).

In Bina Agarwal’s article on ecofeminism, or as she refers to it as “feminist environmentalism,” the main difference between her perception of ecofeminism and that of Karen Warren and Laura Hobgood-Oster, is stated to be a matter of ideology versus material. Agarwal addresses the commonalities of key elements of most ecofeminist theories, those of which are the connection between the oppression of women and nature, women/nature being inferior to men/culture, women’s efforts link to environmental efforts, and that there is a call to use more non-hierarchical systems in society (Agarwal 120). These elements are not unfamiliar and can also be found in the perceptions of Warren and Hobgood-Oster. However, Agarwal goes further to express her belief that ecofeminism in the West has ignored material influences, such as class, race, and lived experiences with nature (Agarwal 122-123). Agarwal also argues that Western ecofeminism generalizes women into one large category without recognizing the impacts of intersectionality on the impacts of environmental degradation, and that it almost gives off the idea that the link between women and nature is essentialist (Agarwal 122-123).

I personally find that the perspective of Bina Agarwal more intriguing due to her use of the word “material” when describing the differences. Agarwal advocates for a more experience-based approach to ecofeminism, taking into account the lived realities that different demographics of women to examine how gender and class play into the environmental changes and their responses to it (Agarwal 126). Last week when I read a post by my classmate Mandi, she raised the excellent point of intersectionality playing a part in ecofeminist thinking that I had not previously considered. With Agarwal’s perception of ecofeminism, it becomes more clear that not every person has the same relationship or experiences with nature, and are impacted in much different ways based on their gender, geographical location, race, and class/caste. I do find that the ideological theories presented by thinkers such as Karen Warren and Laura Hobgood-Oster are very beneficial in terms of identifying thoughts and oppressions that can’t be physically seen, especially through Warren’s connections. Pairing with Agarwal’s experiential take on ecofeminism, I feel as though it would benefit the cause of ecofeminism to not only examine what it believed about the oppressive link of women and nature, but also to see it in real-time to further challenge, as Agarwal states, notions made about gender and the environment’s purpose, as well as the material division of labor and resources based on gender, and the human use of the environment’s resources (Agarwal 127).

Sources:

Agarwal, Bina. “The Gender and Environment Debate: Lessons from India.” Feminist Studies, vol. 18, no. 1, 1992, pp. 119–158. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3178217. Accessed 9 Feb. 2020.

Daza, Vanessa. “Two Fights in One: Feminism and Environmentalism.” Dejusticia, www.dejusticia.org/en/column/two-fights-in-one-feminism-and-environmentalism/.

Shiva, Vandana, and Scott London. “In the Footsteps of Gandhi: An Interview with Vandana Shiva.” Global Research, 3 Feb. 2016, www.globalresearch.ca/in-the-footsteps-of-gandhi-an-interview-with-vandana-shiva/5505135.

UN-Water. “Gender: UN-Water.” UN, www.unwater.org/water-facts/gender/.

Test