When thinking of the concept of intersectionality, my mind used to always go toward the traditional feminist concepts of intersections of sex, race, gender, and so on. With the integration of ecofeminist theory, it has become more clear that the environment impacts social identities differently, while also being oppressed itself. Upon taking this course, intersectionality and feminism in general seems to have more of a presence in ecological oppression than I had initially thought. According to A.E. Kings, intersectionality had not explicitly been explored in ecofeminism as a framework of thought, and some ecofeminist thought continues to solely focus on the link between ecology and gender, rather than overlapping oppressions (Kings 1). However, it can be noted that many works insinuate intersectionality such as the writings of Laura Hobgood-Oster.

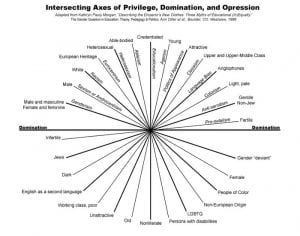

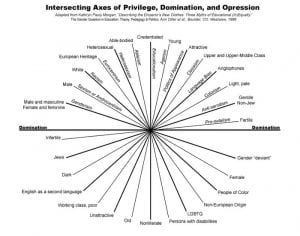

Intersectionality, as defined by the masses, was a term officially coined by Kimberle Crenshaw in 1989 to describe the overlapping of social oppressions that black women faced due to race and gender. It has since evolved into encompassing feminist idea based on sex, gender, race, religion, age, dis/ability, and other forms of discrimination (Kings 1). It is a framework of analysis that allows for a broader idea of what struggles people face based on their social identities rather than having a narrow, single-line type of view at oppression. When ecofeminist theories implement intersectionality into the ideas of ecological oppression, it allows for a discussion of the oppressions that face not only women and the environment, but the oppressions faced by human and even non-human beings and the environment. I loved the example that Kings describes in her work, by using a web. The spokes of the web represent the different types of social identities, while the spirals that interconnect with the spokes of the web represent individual identities. The spirals collide with the spokes at different levels, making it so each individual identity has its own complex experience with disadvantage or advantage (Kings 1).

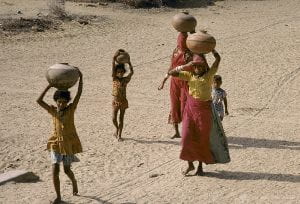

I recall reading in Laura Hobgood-Oster’s writings about forms of discrimination connecting. “Classism, racism, sexism, heterosexism, naturism and speciesism are all intertwined (Hobgood-Oster 2).” When considering this, it makes me think back to the blog I posted about women in the Global South being disproportionately impacted by environmental degradation than most other populations in the world, and how intersectional analysis played a large part in this (UNWater 1). As Kings stated, there often lacks the understanding of more than just gender in ecofeminism, mainly playing on the idea that women and nature are connected. When considering “women,” it feels like a blanket statement that generalizes all women and their experiences instead of highlighting the individual dis/advantages they may face based on social identity. That is why the women in the Global South, being women and people of color of low socioeconomic status are often overlooked in ecofeminism. Not only women in the Global South, but as Cacildia Cain discusses in her article, black women are also seemingly left out of the mix. Cain details the struggles that black women face in the ongoing issues of the Flint, Michigan Water Crisis, and how classism and racism also play a large part in suppressing these women in their environments (Cain 1).

It is crucial for ecofeminism to encompass an intersectional standpoint due to the fact that women should not be generalized, and that the issues are not exclusively female. Although it is theorized that women’s patriarchal oppression is directly linked to the oppression of nature, it can also serve for interpretation of the varied oppressions among all social identities. Myself as a white woman in a “first world” nation does not have the same experience of the environmental impact that a woman in the Global South has, without an adequate water source available immediately and faces a multitude of negative impacts to simply obtain water.

Sources:

Cain, Cacildia. “The Necessity of Black Women’s Standpoint and Intersectionality in Environmental Movements.” Medium, Black Feminist Thought 2016, 23 Oct. 2018, medium.com/black-feminist-thought-2016/the-necessity-of-black-women-s-standpoint-and-intersectionality-in-environmental-movements-fc52d4277616.

Hobgood-Oster, Laura. Ecofeminism: Historic and International Evolution . 18 Aug. 2002.

Kings, A.E. “Intersectionality and the Changing Face of Ecofeminism.” Ethics & the Environment, vol. 22 no. 1, 2017, p. 63-87. Project MUSE muse.jhu.edu/article/660551.

UN-Water. “Gender: UN-Water.” UN, www.unwater.org/water-facts/gender/.

Villalobos, Briana. “Intersectional Ecofeminism: Environmentalism for Everybody.” IWW Environmental Unionism Caucus, 26 Feb. 2017, ecology.iww.org/node/2100?bot_test=1.

This source provided an insight into how environmental issues are experienced differently based on intersectional social identities, as well as factors such as location. Villalobos discusses how the use of intersectionality was lacking in the mainstream feminist movement, and challenges this theme and attempt to use a more intersectinal framework to combat issues for feminism, environmentalism, and the LGBTQ+ movement.